“To decolonise is to remember”: Contemporary art and the decolonisation of the Western world

Introduction

From a young age, the history we were taught was selective. In most Western countries, history is manipulated to promote nationalism and when history cannot be altered to fit this agenda, it is ‘left out of the picture’ (Grant & Price et al., 2020, p. 39). Art is a powerful tool, it is a universal language that can communicate important messages and, in the words of Yinka Shonibare, ‘start[s] debate and can change thinking’ (Shonibare, 2020). This idea of using art as a tool to assert a history that has been forgotten is a form of decolonisation. The term ‘decoloniality’ has been widely used in recent years and is most commonly co-opted by educational and art institutions as a misconstrued form of ‘diversity and inclusivity’ (Grant & Price et al., 2020, p. 16). Despite the words current surge in use, ‘decolonisation’ was initially coined, in the 1930’s, ‘as the retreat of European colonialism’ (Irwin, 2015). The definition has since evolved and is used in art discourses as a way of reviewing the art canon, ‘questioning its ability to include different voices or perspectives’ (Cielatkowska, 2020). Kevin Lamoureux’s definition of decolonisation is particularly informative, he states that ‘decolonisation is about recognising, challenging and ultimately dismantling power structures that oppress the colonised’ and acknowledging ‘those tools of oppression and exploitation…continue to harm people’ today (Lamoureux, 2022).

The aim of this thesis is to identify how Contemporary art can be used as a tool to decolonise the Western world. Each chapter explores important platforms that can be used to shape decolonial processes such as, museums, statues and allyship. The chapters explore three overarching research questions; how do Contemporary artists in the Western world use art as a form of decolonisation? Why are the spaces/locations in which Contemporary art is displayed important? And why is allyship core to the development of decoloniality in the Western art world?

The majority of sources used in this thesis are dated around 2000-2022 as the topic of decoloniality within the socio-political context is relatively new. Moreover, online videos of debates and talks as well as journal articles are the main sources of this thesis as there was a lack of books that covered decolonial thinking in Contemporary artistic practice. In particular, Catherine Grant & Dorothy Price’s Decolonizing Art History journal article and Sumaya Kassim’s essay The museum will not be decolonised (and additional critical sources), frame the analysis of case studies and themes explored in this text.

1: Can museums be decolonised through Contemporary artistic practice?

There is often the assumption that museums are ‘neutrally objective venues of historical truths’ (Onciul, 2017, p. 4) as they showcase artefacts from the past using uncomplicated and simple approaches, for example, categorised by time period and/or geographical location. However, in recent years the ‘unbiased’ nature of museums has been contested in modern museology and art history discourses as, at the very core, museums are plagued with ‘power and authority’ (p. 3). They assert dominance through the manipulation of public perceptions through a curatorial ‘Western cultural lens’ (p. 4) and are heavily embedded with biases that need to be dismantled, as only then can systemic change occur, doing anything less is playing a role of ‘tepid diversity’ (Hasinah, 2022). The question remains, how can museums and galleries be decolonised? Using ‘well-chosen, and well-interpreted, Contemporary art in special exhibitions’ within museum spaces is an effective way of ‘engaging visitors intellectually and emotionally with subjects that otherwise might be seen as remote from their own personal experience’ (Frost, 2019, p. 496). Museums are ‘mirrors and shapers of culture, nations and peoples’ (Onciul, 2017, p. 3), inviting groups and communities who have long been excluded from museum and gallery narratives to curate and exhibit within public institutions can be viewed as an attempt to decolonise.

Traditional museums have long spoken for others and in recent years have come under pressure to allow communities to speak for themselves (Onciul, 2017, p. 7). An example of this is the Re-imaging Captain Cook: Pacific perspectives exhibition at The British Museum in 2018 which intended to consider the ways in which James Cook has been ‘interpreted through time’ (The British Museum, 2019, p. 6). The Contemporary art pieces displayed in conversation with artefacts from the Pacific Islands aim to open discussion on the colonial brutality that followed Captain Cook’s ‘discovery’ and how it affects Indigenous people today. Michael Cook’s photography series Civilised ‘explores how European explorers viewed aboriginal people’ (Cook, 2018). In Civilised #12 (figure 1) the female figure adorns clothing from the Victorian era this feature is particularly poignant as it relates to the representation of Aboriginal people in colonial paintings created between 1850-1900. Roderick Peter MacNeil highlights that clothing Aboriginals, so they resembled Europeans, ‘served as a colonial desire to promote Blacks as being tamed’ and furthered the ‘colonial desire to regulate the appearance of Aboriginal people’ (MacNeil, 1999, p. 167). Cook presents the female figure as she would be represented during the colonial period, bringing forth the idea of the ‘other’, as Aboriginal people ‘were considered inferior’ and in order to be treated like human beings and perceived as ‘civilised’ they had to resemble Europeans (Queensland Art Gallery of Modern Art, n.d.).

Figure 1: Michael Cook, Civilised #12, 2012, Inkjet print, 100.0 × 87.5 cm (image) 120.0 × 108.0 cm (sheet), This is no fantasy gallery, Melbourne, Australia.

An important visual element in Civilised #12 is the recreation of the symbolic Madonna image. The female figure poses breastfeeding her baby, this universal and human act asserts to audiences that Aboriginal people are human beings, contradicting the explorers and settler-Australian perspectives of native Australians as sub-humans and savages. Cook draws his audience in further as looking closely, they can identify that the baby is in fact a doll. The symbolism of using a fake baby relates to the ‘stolen generation’ (Lennard, Murray, & Kosmalska, 2019) where Indigenous children were stolen from their parents and rationalised by various governments claiming it was for their protection, ‘saving them from a life of neglect’ (O’Loughlin, 2020). The absence of a real child in Civilised #12 is powerful and recovers a painful history and psychological trauma that has been passed down generationally. Cook’s restaging of the past, encourages dialogues in our present as well as conversations about the future for all Australians (Queensland Art Gallery of Modern Art, n.d.), as the process of revealing the past through powerful imagery in the Re-imaging Captain Cook: Pacific perspectives exhibition centres Indigenous voices at the forefront of colonial discourse.

More so, the colour and lighting, in Civilised #12, produces an eeriness through the unsaturated, dull tones of the beach landscape, creating a ghostly feel to the image as the sea fades into white hinting to a lack of life. Further to this, the faded background camouflages the written words of William Dampier, in the top left corner, where he recalls his interaction with Aboriginal people stating, ‘they have no houses but lie in the open air, without any covering; the earth being their bed, and the heaven their canopy’. Cook’s choice to embed an explorers perspective into the photograph is a reminder that these words are part of history and should not be forgotten. It acknowledges a European perspective that heavily influenced and changed the lives of Indigenous people forever – this is reinforced through the handwritten font that illustrate Dampier’s words. The handwriting implies subjectivity as rather than it being presented as a passive voice it holds a sense of responsibility and accountability. The words dissolve into the bleak seascape allowing audiences to focus on the Aboriginal figure and her story that represents many.

The exhibition lacks ‘Pacific perspectives’ as the curation, layout and language used in the exhibition reinforces the view that it was created from the point of view of The British Museum (Stooke, 2019). This is embodied through the museum’s narration of Captain Cook’s voyages presenting deeply embedded imperialist language as the voyages are described as ‘extraordinary’ (Stooke, 2019) – almost glorifying Cook’s legacy. Moreover, encounters between Cook and the Indigenous people were described as ‘uneasy’ which essentially reinscribes a justification of Indigenous history as Cook’s ‘voyages are intrinsically bound with colonial history and imperial expansion’ (McLaren & Clark, 2019). The choice of the word ‘uneasy’ within this context understates, degrades and de-legitimises the violence, genocide and years of oppression of Indigenous people that ensued from the explorers arrival and continues today. These examples reinforce the power of language as although the Contemporary art created by Indigenous Pacific Islanders help communicate the importance of acknowledging the past in order to understand our present, The British Museum uses language to subdue and moderate, ultimately creating a narrative that damages the power the Contemporary art holds in the museum space.

Critics Annemarie McLaren and Alison Clark suggest that ‘Cook acts as a prompt for ongoing reflections about the past, present and future’ (McLaren & Clark, 2019, p. 423) implying a need for Cook’s legacy to be part of the exhibition in order to understand why Indigenous artists are making art that re-imagines and responds to Captain Cook. However, the undeniably strong focus on Cook and his legacy, especially in the narration displays, pushes Indigenous voices to the back – in an exhibition that was intended to act as a platform for Indigenous interpretations. Furthermore, The British Museum’s exhibition aimed to open conversation on Britain’s colonial past – which can be an ‘effective catalyst for opening up a space for dialogue with the potential for attitudinal change’ (Frost, 2019, p. 499). However, the lack of Indigenous people involved in the curation of the exhibition reinforces the argument that the museum cannot be decolonised even though the exhibited art arguably successfully decolonises, through remembrance of the past (Kassim, 2017), the layout, language and presentation of objects has been brought together/curated through a Western perspective. For instance, ‘the importance of individual objects within their specific culture is flattened’ leading audiences to view the artefacts as ‘trophies and trinkets’ (Stooke, 2019) rather than as cultural artefacts. Museums intending to explore marginalised perspectives must allow for Indigenous self-representation through curation – as it empowers marginalised people (Ames, 2006, cited by Onciul, 2017, p. 8). This empowerment involves exercising ‘ownership over the stories told in public spaces’ creating potential for ‘meaningful change’ to happen to ‘a seemingly unchangeable system’ (Wajid & Minott, 2019, p. 25). Overall, Contemporary art, within the context of museums exhibitions, cannot successfully decolonise because these institutions ‘are so embedded in colonial history and power structures that they end up co-opting and collecting decoloniality’ (Kassim, 2017) under the façade of diversity and inclusion.

British museums ‘control representation’ over Britain’s former colonies (Wintle, 2013, p. 190). This dominance over colonial narratives creates uncertainty on whether Contemporary art can ever successfully decolonise museum histories within Western museum spaces. As such, Contemporary art responding to the narrative and history attached to artefacts that lie within museums – outside of the museum setting can be viewed as a more effective tool of decolonisation. For example, Yinka Shonibare’s Unintended Sculpture (Donatello’s David and Ife head) incorporates The Ife Head, an African sculpture, that remains in The British Museum against the body of Donatello’s David which has been covered in a Dutch wax design. Shonibare’s inclusion of The Ife Head with the body of David opens conversations around what is considered art and what are considered objects. This is uncovered in the history behind The Ife Head’s as the German explorer, Leo Frobenius, visited West Africa and came across The Ife Heads’ and was sure he had discovered remains of the mythical lost city of Atlantis, ‘refusing to believe that the sophisticated and ornately carved bronze sculptures were made in Africa.’ (Busari, 2010). Shonibare incorporates Donatello’s statue David to critique the idea that Africans could “not have made a work that beautiful in bronze” that it was something “Donatello would have made” (John, 2022).

Figure 2: Yinka Shonibare MBE, Unintended Sculpture (Donatello’s David and Ife head), 2021, Fibreglass sculpture, hand painted in Dutch wax pattern, patinated bronze, gold leaf, 154.5 x 57 x 58cm, Stephen Friedman Gallery, London, United Kingdom. Photographed by Stephen White & Co.

Additionally, the vibrant patterned body is juxtaposed with the deep green/bronze toned re-creation of The Bronze Head fromIfe, which unlike the rest of the body is presented in similar colours to the original. The Western ideal that African artists of the time could not create something that is worthy of Western audiences fuels the meaning behind the work as Shonibare choosing to keep The Ife Head similar to the original is an ‘honour to the invisible’ (Tanya & Lejeune, 2018, p. 13). The combination of The Ife Head and the body of Donatello’s David is a powerful comment on two cultures of heritage and highlights what is perceived as art and what is viewed as an object with no maker/artist attached. Rose Lejeune explores this concept in the exhibition of art in museums where non‑Western artefacts are ‘identified by material… geography and time but not artist or maker’ (p. 12). Furthermore, by replacing the head of Donatello’s David with The Ife Head is to acknowledge and recognise the art created by the Ife people as ‘faces are usually the first thing we notice’ and ‘tell us more than any other physical attribute’ (Solso, 2004) – focusing the audience’s attention to a non-Western art piece, essentially dismantling the Western Eurocentric lens art is almost always viewed through.

Additionally, the body of the statue is covered in a Dutch wax pattern, known as ‘fabric of the African diaspora’ (Canales, 2021), synonymous with African identity which gained momentum in the 1960’s in the wake of decolonisation (Kent et al., 2014, p. 7) and is a constant visual feature in Shonibare’s body of work. The history behind the fabric is core to Shonibare’s practice as he explains the fabric was influenced by Indonesian batiks that were later ‘mass produced’ (Downey, 2014, p. 43) by the Dutch to sell back to Indonesians but were largely unsuccessful. The prints gained popularity in West Africa instead resulting in the fabric’s association with ‘Africanness’ (Kent et al., 2014, p. 43). The body of Donatello’s David being used as a canvas for the Dutch wax patterns is significant as the sculpture was ‘the first bronze male nude and the first free-standing statue’ (McAloon, 2018). The visual imagery created in the painted Dutch wax fabric pushes forgotten history, in particular, the interrelationship between Africa and Europe as a result of colonialism (Shonibare, n.d.) to the forefront of discussion around the piece – and asserts an importance as it is presented on one of the most significant works in Western art history.

Unintended Sculpture not only addresses European evaluations on what is considered ‘high’ and ‘low’ art (Auger, 2000, p. 89), it challenges ‘Western museums and institutions that have previously permanently imprisoned or enslaved artworks from former’ colonies (Grant & Price et al., 2020, p. 33). This act of challenge is a form of decolonisation as the sculpture reveals a forgotten colonial history and intertwines the past and present. The Ife Head, like the majority of Western museum collections, ‘has a double historicity…its existence before and after the act of accession’ (Hicks, 2020, p. XIV), for example, it holds important cultural history on the ancient African city of Ife as well as revealing methods of looting and pillaging which ‘were of central importance’ during militarist colonialism (Hicks, 2020, p. 23). This encourages an examination on the past; how the British came to poses the artefact as well as scrutinizes the present; why, like thousands of other looted artefacts, its location in The British Museum today is problematic.

Overall, Shonibare’s sculpture is to a greater extent successful than Cook’s Civilised #12 as although both pieces acknowledge the past and encourage important conversations in our present, the setting of the museum, in which Cook’s art was exhibited, plays a key role in the way the art is understood. Writer Sumaya Kassim states that ‘museums trick audiences into believing colonialism is all in the past…the lighting, the labels, the white walls all promote forgetfulness and fantasy. (Kassim, edited by Aburawa, 2018). Re-iterating that because Western museums have deeply embedded colonial ideals, the museum space can never encourage the process of decoloniality as ‘decolonisation needs to literally un-settle colonial spaces’ (Grant & Price et al., 2020, p. 29) which cannot occur when the art exhibited and the presentation of artefacts within museums is being framed through a Western imperial lens. The question remains, if museums are not an effective space for conversations on decoloniality, what other public spaces can be used as a platform for decolonial thought, and how can Contemporary art play a role?

2: Combating the revering of statues/monuments – how are Contemporary artists decolonising public spaces?

The process of decolonising museums opens further dialogue on how societally we come to terms with violent pasts in other public spaces (Burch‐Brown, 2020, p. 809). Statues and monuments are ‘erected to preserve a memory’ (Gregory, 2021, p. 564), they iconify figures that were viewed as heroes in the past. Many view statues as big boulders that we walk past and barely give ‘a second glance’ (p. 580) – while simultaneously acknowledging the importance of the person memorialised. It is this very reason that discourses around revering or removing statues have been at the forefront of socio-political debates. The call for the removal of statues along with the defacement of statues, has grown widespread in recent years and gained momentum during the ‘Rhodes must fall’ campaign in 2015 (Chaudhuri, 2016). Cape Town university students led protests for the removal of the Cecil Rhodes statue on campus due to the brutal legacy of Rhodes as an ‘avowed White supremacist and staunch imperialist’ (Timalsina, 2021). As a result of continuous protests, the statue was removed within a month, this momentous achievement was a catalyst for the scrutinization of problematic statues around the world. The debate on removing statues is complex and the ideas shared, both for and against holds value. For example, Afua Hirsch writer of Brit(ish) (2018) aligns with the removal of statues commemorating racist and imperial figures, highlighting that the act of craning our neck to look up at these statues on plinths is in itself ‘an act of reverence’, arguing that they ‘should be in a place where there is an educational process, genuine conversation and context’ (Intelligence Squared, 2018). However this argument is countered with the idea that pulling ‘statues down…would distort history’ (Gregory, 2020, p. 586), and is ‘an attempt to erase and hide evidence of past wrongdoing’ (Burch‐Brown, 2020, p. 814). Voices within this debate have also suggested adding plaques that add context to the statues, however, plaques are usually small and ignored when passing by. Instead Contemporary art can be used to recontextualise controversial monuments and could be viewed as more effective way of remembering, as ‘the work of artists challenges our conventional ways of viewing and interpreting public sculpture’ (Hatt, 2022, p. 5) and is an act of loudly reclaiming public spaces.

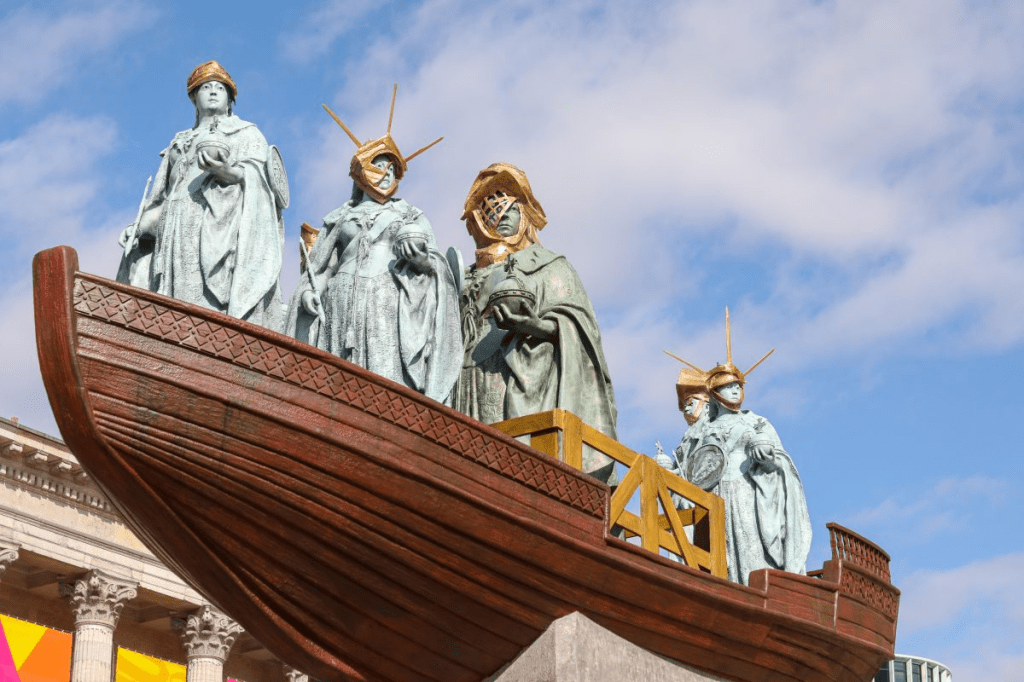

Figure 3: Hew Locke, Foreign exchange, 2022, resin, Birmingham, United Kingdom. Photographed by Shaun Fellows.

During Britain’s colonial expansion, statues were not only placed in Britain to commemorate officers and ‘heroes’ for the public to look up to, statues of important figures were also shipped to colonies. Most notably, statues of Queen Victoria ‘were shipped around the world as a representation of empire’ (Ikon Gallery, 2022). In Guyana a statue of Queen Victoria was commissioned in 1894 to mark the monarch’s golden jubilee. The statue resided in front of Georgetown’s law courts, however, after Guyana became independent from British rule, the statue was beheaded, and the remains were thrown into bushes of the botanical gardens (Drayton, 2019, p. 14). Artist Hew Locke recalls passing the statue while growing up in Guyana and was shocked that the statue was vandalised, prompting him to question ‘what public statues are for’ and ‘how come we pass by them without noticing every day?’ (Stuart, 2022) in his temporary public sculpture Foreign exchange. The art piece was commissioned for the 2022 Birmingham Commonwealth Games and was created to encompass the Queen Victoria sculpture in Victoria Square, Birmingham. Most notably there are five additional Queen Victoria sculptures added to the original that are all encompassed within a large wooden boat – visually referencing the shipping of Queen Victoria statues to the colonies (Commonwealth sport, n.d.). Over time the statues within these countries have become a symbol of the Crown’s complicity in the ‘history of violence, attempted genocide, and theft’ (Hatt, 2022, p. 2). Locke’s installation reimagines and encourages the public to view the statue through a post-colonial lens – where instead of a memorialisation or celebration there is reflection and an uncovering of the past.

Each statue in Foreign exchange adorns a gold martial helmet, varying from replicas of Britannia’s helmet to the Statue of Liberty’s and ‘the original Victoria has been crowned with a gladiator-like helmet with a visor across one eye’ (Stuart, 2022). The inclusion of the helmet worn by Britannia is poignant and reinforces the similar imagery shared between Queen Victoria and the embodiment of Britannia. Imagery of Queen Victoria iconised her ‘as the maternal heart of the British Empire’ both ‘familial and familiar’ (Plunkett, 2022, p. 2). Similarly, Britannia was fashioned for ‘strident propaganda for the justness of British rule’ (Jackson & Tomkins, 2011, p. 174) holding the same maternal yet powerful connotations as Queen Victoria, playing an important role in the way The ‘British Empire modelled itself at home and abroad’ (Plunkett, 2022, p. 2). These images contributed to an ‘over-romanticising of Queen Victoria’ even though she ‘supported her troops in several dubious foreign campaigns and wars’ (Ikon Gallery, 2022). Thereby, the striking addition of Martial helmets on the Queen Victoria statues creates a juxtaposition. The image of the ‘dutiful mother and grandmother of nation and empire who has given everything’ (Hatt, 2022, p. 2) is replaced with a more reliable and realistic version that perpetuates violence and power.

The statues presented medals of colonial wars (Ikon Gallery, 2022). For example, a medal commemorated; ‘the British East India Company’s defeat of Tipu Sultan’; one ‘marks Britain’s calamitous second Afghan war of 1878-80’ and another ‘memorialises the British soldiers who looted the Benin Bronzes, now held in The British Museum’ (Stuart, 2022). The recognition of these events highlights how Foreign exchange encourages ‘multiple truths and perspectives’ to ‘collide and coincide’ (Drayton, 2019, p. 15). Particularly, the inclusion of the Benin bronzes within the sculpture reveals the ‘association between The British Museum and colonial looting’ (Frost, 2019, p. 489), opening conversations around the contents of British museums and how stolen artefacts are displayed –for example, the writing accompanying artefacts does not inform audiences how they were acquired.

Furthermore, by ‘reviving the memory of these brutal conflicts in a public space, Locke challenges the favoured representations of Empire’ (Baksh, 2022) and presenting these medals onto the original Queen Victoria statue creates a sense of accountability for the brutality of The British empire and the role Queen Victoria played. The medals appearance blended into the aged bronze statue replicas, this visual integration of forgotten history onto such a celebrated figure encourages audiences to think about who should and shouldn’t be memorialised (Intelligence Squared, 2018). This prompts audiences to ‘dig deeper’ and ‘empowers people to ask questions around not only history, but the power and purpose of monuments’ (Baksh, 2022). The recalling of important wars and imperial conquests onto medals is symbolic as medals are usually associated with honour and doing good. This contrast creates tension between the content of the medals and the meaning behind medals – pointing to the history of celebrating colonial conquests and how, even today, critique of The British Empire is dismissed institutionally (Jasanoff, 2020).

Further to this, The Queen Victoria statue, despite its location, is ‘often overlooked – so familiar that it becomes invisible’ (Commonwealth sport, n.d.). Locke reimagines the sculpture and draws new attention to it through the scale of Foreign exchange. Scale plays an important role in how art is perceived, If Locke added a small feature to the original, the public would likely not notice the new addition. Instead, Locke encompasses the original almost disguising it amongst the replicas creating a focus on the narrative of the sculpture. In a debate where keeping or removing statues is at the centre, Locke and other Contemporary artists are proposing a different solution – art. Overall, Foreign exchange is ‘quiet radicalism at its best’ (Baksh, 2022), it is subtle in a way that is powerful – forcing people to stop in their tracks, to look up and remember instead of revere, essentially decolonising public statues.

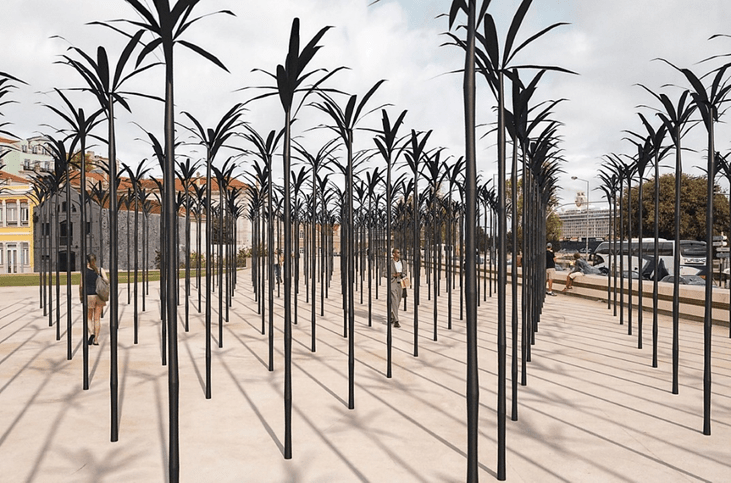

Similarly, monuments are often erected to ‘promote selective historical narratives’ focusing on ‘convenient events’ while obliterating discomforting realities (Bellentani & Panico, 2016, p. 28). Angolan artist Kiluanji Kia Henda dedicates ‘his work to reflecting on monuments as places of struggle’ and ‘collective memories’ (Plasencia, 2021). Henda re-claims public space in his art installation Plantation (memorial to the enslaved people) paying ‘tribute to the millions of Africans enslaved by Portugal throughout its history’, creating a ‘place of memory and open reflection’ (Silva, 2020). Henda’s Angolan heritage plays a large role in the meaning behind the sculpture as ‘for over 250 years Angola was regarded as the principal slave market for Portugal’s empire’ (Boxer, 1963, p. 28). Plantation is formed of 540 black aluminium sugar cane sculptures reaching to three meters in height (Silva, 2020). The representation of sugar canes is symbolic as it recalls Portugal’s involvement in the trans-Atlantic slave trade. Additionally, the sugar cane has become synonymous with slavery due to sugar cane plantations, most notably, it shares an important history with Portugal as the Portuguese ‘took control of worldwide sugar production in the 15th century as an economic by-product of their exploration and colonization of the Atlantic Islands along the African coast’ (Hancock, 2021) and ‘although slave exports were prohibited in 1836’, slavery remained ‘in Portuguese territories in West Central Africa until 1869’ (Candido, 2020, pp. 91-92). The absence of Portugal’s colonial history in school textbooks is ‘but one of the several instances that illustrates Portugal’s inability to address’ the country’s ‘historical legacy’ (Santos, 2020, p. 47) which Henda addresses in Plantation.

Figure 4: Kiluanji Kia Henda, Plantation, 2021, aluminium, Campo das Cebolas, Lisbon, Portugal

The location of Henda’s Plantation is the memorial’s most crucial feature, it resides in Campo das Cebolas, in front ‘of the port where slave ships docked’ (Plasencia, 2021). The physical reminder that the memorial is at site of such historical importance connects to the meaning behind the installation, encouraging ‘memory preservation’ (Lança, 2019) ‘open to reflection’ (Silva, 2020). Henda’s public installation is a visual manifestation of remembrance, it recalls a history that Portugal has failed to acknowledge for centuries. This pattern of social and institutional ignorance can only be broken through education and while its Government refuses to address and change how Portugal’s colonial “discoveries” are taught in school, Contemporary artists, like Henda, are taking back control of narratives through art (Sousa, 2021). Notably, 30 minutes away from Plantation lies Padrão dos descobrimentos (The Monument of Discoveries)[1], ‘one of the most visited and photographed memory sites in Contemporary Portugal’ (Sapenga, 2008, p. 26). Viewing The Monument of Discoveriesin person does not compare to photographs of the monument, ‘the grandiose proportions of the larger-than-life figures’ (p. 26) towers over onlookers. The position in which the monument is placed is also intresting, it faces the sea extending over the coast, meaning that viewers standing next to the monument can only view the sides leaving the front of the monument only visible from the sea at a distance – due to its enormous scale. As explored in Locke’s Foreign exchange, scale is important and being large enough to stop the public in their tracks plays a vital part in the way the art piece is perceived. The Monument of Discoveries, on the other hand, is extremely large making audiences unable to view the monument at all angles. This physical restriction is a metaphor for many colonial monuments, where audiences are only shown one part of the history, forcing a singular perspective.

Unlike The Monument of Discoveries, Plantation physically encourages a reflection of the past, as audiences are able to walk through the monument and be encompassed both in thought and physically in the sugar cane plantation. Aesthetically, the sugar canes are simple, identical and stand equidistant to each other allowing audiences to focus on the meaning behind the memorial rather than focus entirely on the visual properties. This does not mean to say that the memorial is any less impactful because of its uncomplicated nature, instead, the bleakness of each sugar cane sculpture creates an eeriness almost as if the sugar canes represent bodies. Henda uses density as a way of visually representing Portugal’s heavy history, the opaqueness of the sugar canes allows for shadows to be clearly projected onto the floor where the sculptures stand – this adds to the expansive nature of the installation and creates a further sense of uneasiness through density.

Although Henda has not built directly onto The Monument of Discoveries, there is a link between the two sculptures not only in terms of location (both reside on the same coast) but through the topic of colonialism. Henda’s installation recalls a painful history of colonialism and slavery, whereas The Monument of Discoveries censors. Instead, an idealised version of Portugal is represented as, even in its title, the term colonialism is replaced with the word ‘discoveries’ and the figures represented on the monument are revered as contributors to the ‘discoveries’. The Monumentis described as ‘the past recapitulated’ and ‘made present’ (Sapega, 2008, p. 26), on the contrary, the past in which the monument aims to uncover is ‘inevitable biased’, as a selective narrative of colonialism is presented to audiences (Cobley, 2001, cited by Bellentani & Panico, 2016, p. 33). Monuments are built to educate and if the ‘history’ they are informing audiences with is a celebration rather than a reflection, artists have the opportunity to challenge this and communicate a ‘strong path of remembrance’ (Lança, 2019). Without this reflection that Western monuments avoid, ‘our imaginary becomes an accomplice to denials of violence that can always be repeated in unexpected ways’ (Lança, 2019). Plantation uncovers the past to ‘establish a link’ (Fernandes, 2020) to our present as only through remembrance and education can the possibility of the past repeating itself be avoided, as while misinformation and rose-tinted versions of history still remains unchallenged in monuments and statues, racism will continue.

To decolonise public space is to reveal, educate and reflect on a past that has been erased. If we learnt about ‘the full historical record of the figures being memorialised, it would matter less that these statues are on their plinths – However, we have no context and we have no education, instead we live in a place that reveres them’ (Hirsch spoken in Intelligence Squared, 2018) making monuments ‘innocuous bystanders in the urban landscape’ (Marschall, 2017, p. 685). Although both works decolonise, it is important to note that decolonisation is an ongoing process and, when discussing public spaces, can only be sustained if the acknowledgement is permanent. In regard to the Contemporary artwork discussed above, Foreign exchange was a temporary installation on the Queen Victoria statue, in contrast, Plantation’s permanence cements the installation as a continuous force of decolonisation. Despite this, thirty minutes away The Monument of Discoveries, visited by thousands of people, sits in its original form, holding the same connotations it held when it was built. Highlighting that until problematic statues and monuments are physically addressing the past permanently, the removal of problematic statues/monuments appears to have a stronger sense of decolonisation. The irony is that the act of destroying statues has taught us more about public history than statues’ survival ever did (Woods, 2020, p. 18). Those who have argued that the removal of statues is an erasure of history forget that ‘the monument itself has already erased history’ and the presence of controversial figures being promoted as a person to admire ‘has already silenced the history of Indigenous’ and colonised people (Hatt, 2022, pp. 3-4). The public are being made aware of the history attached to statues that have been toppled/defaced drawing ‘attention to the problem’ – making it a powerful form and expression of decolonisation (Marty, 2020).

[1] Leopoldo de Almeida, Padrão dos descobrimentos (Monument of Discoveries), 1939, concrete, Leiria stone, limestone, Belem, Lisbon, Portugal

3: How can White-saviorism discourage and allyship encourage decoloniality in the Western art world?

When statues and monuments are toppled down, what should replace empty plinths and who should be given the opportunity to reclaim these public spaces? Who should be chosen to take control of narratives that have long been erased from history? Many artists use their privilege to bring attention to injustices, there is however, a fine distinction between amplifying voices and shouting over and louder than those who were already speaking. In order to understand the difference we must evaluate how artists and institutions (museums & art galleries) are becoming allies and, as a result, actively encouraging decoloniality within public spaces in the West. The term ‘ally’ has grown in popularity over recent years, it describes someone ‘who advocates and works alongside’ minorities and is a person ‘who learns to actively listen’ (Reid, 2021). Graciela Mohamedi’s TED talk ‘screaming in silence’ explores ideas on allyship, she states that the need to be right first or louder than everyone else is ingrained within us, and when we are the first to be heard someone must be left behind, ‘that someone is almost always a person of colour’ (Mohamedi, 2018). Allyship is void and becomes a form of White saviourism ‘when ‘the “ally” in question centres themselves in the struggle’ (Stevens, 2019), this centring of White voices over minorities fuels erasure of narrative and in turn dehumanises and victimises the colonised as voiceless.

In 2020, George Floyd’s murder catalysed waves of global Black Lives Matter protests. In Bristol, years of campaigning for the removal of the Edward Colston statue ended in a historic moment where the statue was defaced and toppled by protestors. This ‘act of history’ (Woods, 2020, p. 18) heavily influenced the discourse on the decolonisation of statues and monuments in Britain, changing public perception on the purpose of statues and led people to question problematic statues that still stand. Immediately after the statue was toppled the ‘empty plinth once occupied by the slave trader’ Edward Colston (Price, 2021) held a new statue named A Surge of Power by Marc Quinn featuring a black resin sculpture of Jen Reid, a Black lives matter protester who climbed the empty plinth during the George Floyd protests in June 2020. At first the artwork was praised, and Quinn was applauded for using his White privilege to ‘keep the conversation going’ around Black Lives Matter (Wall, 2020). However, many people of colour viewed Quinn’s sculpture as the opposite of allyship, and more as an act of ‘White saviourism…rolled into one sculpted lump of black resin’ (Morris, 2020).

Figure 5: Marc Quinn, A Surge of Power, 2020, resin, Bristol, United Kingdom

The term ‘White-saviour’ describes a narrative where ‘social change [only] occurs through white leadership’ as a result, people of colour ‘occupy primarily the role of the victim as opposed to the victor’ (Cammarota, 2011, p. 249). Quinn’s act is White-saviour and as a consequence, opposes decoloniality as although A Surge of Power features a Black woman (who took part in the historic protests), decolonisation within art history, is centred upon digging beneath the surface. Looking closely at who is making the art? who is curating exhibitions spaces? who is in the room when all these decisions are being made? And, most importantly, ‘who is being heard?’ (Grant & Price et al., 2020, p. 37). Quinn chose to fill an empty plinth, that once stood Edward Colston, with his art making sure his name was connected to the sculpture. The empty plinth was a chance for Quinn to use his privilege and popularity to host other public artworks or literature by people of colour, instead it became an opportunity for Quinn to gain clout ‘from a moment in British history that he played no part in supporting the past 30 years of his lucrative career’ (Price, 2021). Unlike allyship, White saviourism takes the narrative away from minorities – essentially opposing decolonial thinking as decolonisation centres around storytelling. White people can and should use the privilege to help amplify the voices of people of colour, but the way in which it is attempted is crucial. Being an ally ‘isn’t in…politics and spectacle, it’s not in yelling from a stage, the real work begins at the community level, the real work is much quieter’ (Mohamedi, 2018). The space that had been decolonised by the protesters had almost been ‘colonised again…in a way that sabotaged’ the progress that was being made (Price, 2021). Decoloniality is sustained through uplifting marginalised voices who’s stories have been systematically erased and left out of history. Privilege is power, White artists who are actively supporting, amplifying and intensifying underrepresented voices are helping to dismantle and decolonise the Western art world, as, when White privilege is used as a vehicle/platform to strengthen important dialogues societal, institutional and social change is a step closer.

In 2014 a performance installation by Brett Bailey held at the Barbican gallery faced immense backlash creating an online petition and protests calling for the exhibition to be cancelled. The exhibition named Exhibit B[1], aimed to interrogate empire and address ‘the European legacy of whiteness and its relationship with Africa’ (Lewis, 2018, p. 116) by showcasing live Black models in cages, and slave shackles (Holloway, 2014) – essentially re-creating a 18th – 19th century European human zoo. The exhibition overtly revealed the past and can at first be viewed as an act of decolonisation as, ‘to decolonise is to remember’ the past (Kassim, edited by Aburawa, 2018). Despite this, Exhibit B was not an act of allyship as it silenced Black voices both within the exhibition space and through Bailey’s dismissal and disregard for of those protesting and campaigning against the exhibition. Exhibit B held the potential to centre around Black voices and stories. In particular, the story of Sara Baartman, the ‘earliest example of a human exhibit’ (Fennell, 2021), who was taken from South Africa and de-humanised on stages around Europe where people would pay to poke, prod and gaze upon her with ‘wonder, disgust, lust, and scientific curiosity’ (Lewis, 2018, p. 117). Even within hours of her death, her body was dissected and violated further and her ’remains were displayed in Parisian museums until the 1980s’ and ‘only returned to South Africa in 2002’ (Qureshi, 2014). Sara Baartman’s story is among countless others that are yet to be heard and acknowledged, by educational institutions in the West.

Bailey named a room in the exhibition Sara, where a Black woman stood ‘isolated and half-naked on a pedestal, waiting to be examined’ (Qureshi, 2014). Notably, when the installation was shown in South Africa, he removed the installation out of respect ‘not wanting to imitate or represent her in her motherland’ (Lewis, 2018, p. 129). There is a certain irony to this as Bailey had no hesitation imitating her in other countries – using her name without her story attached. Sara Baartman’s story should be remembered but not by a silent, nameless model. Critics claim that Exhibit B ‘created a space of exchange, of dialogue’ (p. 126), however, the models non-verbal act degrades the stories Bailey has loosely alluded to and simultaneously objectifies the Black actors. This ‘objectification was at the heart of human zoos…recreating this re-exoticizes and reproduces the original racism’ (Odunlami & Andrews, 2014). Although the Western art world needs to be ‘a site of radical practice and dissent’ (Grant & Price et al., 2020, p. 12) for decoloniality to take shape, Exhibit B was radical in a way that was damaging as Bailey filled the role of the White saviour. The exhibition narrowed the Black experience ‘by depicting blackness only as suffering’, essentially victimising Black bodies in order for White audiences, to feel ‘guilt, shame, denial or dissociation’ (Molefe, 2014, cited by Lewis, 2018, p. 136). Although guilt seems a justifiable reaction to White people viewing Bailey’s exhibition, White guilt is harmful as it centre’s around making ‘the real problems of Black people secondary to the need for White redemption’ (Steele, 1990, p. 499). White guilt encourages a perception of Black people as victims who need saving, this is not to deny inter-generational trauma but as stated by indigenous activist Jen Green, ‘we would not be alive and still hauling down statues and asserting our sovereignty if there wasn’t an even stronger inter-generational resilience.’ (Green, 2021). To encourage Black people ‘to confront the history of their objectification’ (Atkin, 2015, p. 139) and be reminded of ‘what [their] ancestors went through’ (Holloway, 2014) does not strengthen or encourage decoloniality in the way Bailey and the Barbican gallery directors presumed it would. For people of colour, racism is a daily confrontation, it is part of their past, present and future.

‘Decoloniality is [about] humanising everyone’ (Hasinah, 2020), instead Exhibit B re-emphasised stereotypes, victimised and essentially dehumanised the Black community. Many a time people of colour are having their own narrative written for them, it has become clear that in order for decoloniality to hold weight and cement itself within the Western art world people of colour need to be given the space and tools to take control of their own narratives – something that has been denied from them for a long time. People of colour are not ‘voiceless’ and art, like Bailey’s, that takes that voice away results in the work of people of colour being ‘co-opted at best and erased at worst.’ (Mohamedi, 2018). Although Bailey was the artist behind the exhibition, Barbican gallery gave the ultimate green light for the exhibition, circling back to the responsibility of museums & art galleries and whether they have the potential to evolve into strong allies. Without the weight of public institutions pushing for decoloniality and actively dismantling the structures they were built upon deep rooted societal change is out of reach.

An example of an institution striving to become an ally can be seen in the curation of The Past is Now: Birmingham and The British Empire exhibition at Birmingham museum and art gallery. Six co-creators from outside the museum world were invited to ‘tell a different version of events’, a perspective of The British Empire that had not been experienced in the museum and gallery space before (Minott, 2019, p. 564). The exhibition’s opening rejected the idea of neutrality, addressing that ‘no two countries had the same colonial experience; no two people experienced British rule in the same way’ acknowledging that ‘this complex story cannot be told neutrally’ (p. 569). A statement like this is rarely seen in museum exhibitions, as within permanent displays, The British Empire is always seen through ‘the allusion of false neutrality’ (p. 570). These words displayed in the museum space set a critical tone, re-framing the way the exhibition was received by audiences.

Storytelling is a key tool in decolonial processes, it moves ‘beyond simply eliminating the power hierarchies and practices of colonization’, it facilitates ‘the resurgence of indigenous sovereignty by reclaiming epistemology and knowledge that was previously erased’ (Sium & Ritske, 2013, cited by Samuel & Ortiz, 2021, p. 5). The co-curators of The Past is Now, who were all women of colour, embedded their lived experiences and stories into the museum setting – taking back control of their narrative. This ‘curatorial activism’ dulled out the passive, neutral voice of the museum and instead and gave a ‘voice to those who have been historically silenced or omitted altogether’ (Reilly, 2017, cited by Wajid & Minott, 2019, p. 28).

Figure 6: The Past is Now: Birmingham and The British Empire, 2017, [exhibition], Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery, Birmingham, 2017-2018. Photographed by Shaheen Kasmani.

Although The Past is Now exhibition was successful in many aspects, behind the scenes there were barriers that the co-curators faced and fought against. Most predominantly, there was a sense that the institution was ‘fearful of using an unfiltered version of their voice’ (Minott, 2019, p. 565), for example, the words ‘racist’ and ‘exoticized’ were initially removed from a panel in the exhibition. Co-curator Shaheen Kasmani reflects, ‘if I use the word racist and the museum takes it out, you’re making a statement, you’re saying that my lived experiences are invalid’ (Shaheen, 2018). This political act of editing and attempt to naturalise words to make them more ‘passive’ and less ‘visceral’ (Minott, 2019, p. 565) cements colonial structures – as language plays an important role in the way we understand history. Decoloniality centres around storytelling and if stories are being ‘altered’ to fit into a structure/system that is known for erasing the perspectives of the colonised, the idea that ‘museum[s] will never be decolonised’ (Shaheen, 2018) appears more plausible.

In spite of this, the museum compromised with the co-curators and allowed important words to be displayed in the exhibition. The staff at Birmingham Museum and Art gallery actively listened, encouraging learning – an important part in decolonising process. The co-curators and Museum staff learnt from each other allowing them to carry the knowledge they have gained to ‘proactively address and redress current asymmetries’ (Grant & Price et al., 2020, p. 30) in new projects. The finished exhibition ‘was undeniably moving’, objects were ‘properly contextualized as souvenirs of traumatic histories’ (Kassim, 2017) rather than souvenirs of Britain’s conquests. The Past is Now exhibition reinforces Institutions are flawed allies, nonetheless, they are vital in order for change to occur as they construct narrative and history which shapes public knowledge and understanding. Decoloniality, as shown in The Past is Now exhibition, involves dismantling systems that have, and continue to, oppress colonised people.

In review, decoloniality is not an easy process and is certainly ‘not something that can be completed in a single attempt’ (Minott, 2019, p. 573). Decolonial solidarity is a thoughtful process requiring ‘continuous rethinking, acknowledgement and self-reflection on positionality, power, privilege, guilt and legacies of oppression’ (Walia, 2012 cited by Kluttz, Walker & Walter, 2019, p. 52). Quinn’s A Surge Of Power and Bailey’s Exhibit B hosted by Barbican gallery, were ill-considered pieces of Contemporary art and the artists wilfully ignored criticism that was directed towards them from the communities they sought to ‘support’. White saviourism is ‘framed as benevolent’ (Windholz, 2020) and as a result avoids harsh criticism, without criticism and accountability decoloniality is stunted as ‘not everything that is faced can be changed. But nothing can be changed until it is faced.’ (James Baldwin spoken in Hasinah, 2020).

[1] This thesis will not include any images from the Exhibit B exhibition.

Conclusion

History ‘is written by the winners’ (Eddo-Lodge, 2017, p. 38) – it is this very reason that we have to view history through an unbiased lens, ‘decolonise our minds’ (Hasinah, 2022) and unlearn everything we know and have been taught. Without knowing the past how can we understand our present? How can we think critically about those who came before us and the people in power today? How can we know right from wrong? The decolonisation of the Western art world begins with education, Contemporary art educates and forces us to ‘realise that our beliefs about the world are wrong’ and by seeing ‘our own complicity in systems of oppression, there is potential for radical change’ (Boler, 1999 cited by Kluttz et al., 2019, p. 51).

The case studies discussed reveal three conclusions; firstly, public spaces can work towards decoloniality, however, decolonisation is an ‘ongoing process…there is no point in the future where we will be able to say…we have decolonized art history’ (Grant & Price et al., 2020, p. 40). Decoloniality can be sustained and cemented as evolving decolonial acts through ‘embedding it in the permanent practice’ of institutions (Minott, 2019, p. 571) and if art critically responding ‘to the structures and residues’ of colonialism (Grant & Price et al., 2020, p.19) were made permanent, as opposed to the temporary structures and exhibitions currently circulating in public spaces/institutions, audiences would be compelled to assert the erased histories in their minds.

Secondly, although there are small steps progressing towards decoloniality in public spaces the case studies explored in this thesis return to the same obstacle; the locations where these decolonial acts occur are spaces anchored in histories of deep-rooted colonialism and oppression. In the words of Audre Lorde, ‘the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house’ (Lorde, 2019, p. 105), implying that appropriating ‘existing colonial structures is a futile exercise’ as public spaces are Eurocentric and anything ‘outside of that frame of influence’ is othered (Grant & Price et al., 2020, p. 52) – instead we should work ‘towards [an] establishment of new spaces…that can be customized to our own needs.’ (Kondile & Mabaso & Mistry, 2021, p. 40).

Thirdly, allyship is the foundation decoloniality balances upon – it is fundamental. Without genuine allyship, by artists and art institutions, White saviour acts under the guise of genuine solidarity may take up public spaces instead – doing more harm than good – as seen in Exhibit B. Allyship acknowledges ‘that colonialism was not an event, but a structure that is…consistently present’ (Klutz, Walker & Walter, 2019, p. 55). This understanding is imperative for the survival and evolution of decolonial practices as, while history continues to repeat itself in the colonialism and illegal occupation of ‘Kashmir and Palestine’ (Ross, 2019), decoloniality will forever be relevant.

Overall, the analysis of case studies within this thesis uncovers that Contemporary art demands a ‘radical re-examination of knowledge’ (Mabaso & Mistry, 2021, p. 5) and has the ability to expose the past by forging ‘a strong path of remembrance’ allowing artists ‘to communicate across temporalities and spaces, which traditional historiographical treatment [can] hardly accomplish’ (Lança, 2019). To conclude, analysis of the case studies re-affirm that Contemporary art can effectively decolonise the Western world, however, the contexts behind these artworks/exhibitions such as who the art was made by? where is it exhibited? how it is displayed? is equally, if not more important.

List of images

Figure 1 Michael Cook, Civilised #12, 2012, Inkjet print, 100.0 × 87.5 cm (image) 120.0 × 108.0 cm (sheet), This is no fantasy gallery, Melbourne, Australia.

Figure 2 Yinka Shonibare MBE, Unintended Sculpture (Donatello’s David and Ife head), 2021, Fibreglass sculpture, hand painted in Dutch wax pattern, patinated bronze, gold leaf, 154.5 x 57 x 58cm, Stephen Friedman Gallery, London, United Kingdom. Photographed by Stephen White & Co.

Figure 3 Hew Locke, Foreign exchange, 2022, resin, dimensions unknown, Birmingham, United Kingdom. Photographed by Shaun Fellows.

Figure 4 Kiluanji Kia Henda, Plantation, 2021, aluminium, dimensions unknown, Campo das Cebolas, Lisbon, Portugal.

Figure 5 Marc Quinn, A Surge of Power, 2020, resin, dimensions unknown, Bristol, United Kingdom.

Figure 6 The Past is Now: Birmingham and The British Empire, 2017, [exhibition], Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery, Birmingham, 2017-2018. Photographed by Shaheen Kasmani.

Bibliography

Books

Barringer, T. and Flynn, T. (1998) Colonialism and the object: Empire material culture and the museum. London: Routledge.

Boxer, C.R. (1963) Race relations in the Portuguese colonial empire: 1415-1825. Oxford: Claredon Press, p. 28.

Boxer, C.R. (1969) The Portuguese seaborn empire: 1415-1825. Pelican.

Catalani, A. (2010) Telling ‘another’ story: western museums and the creation of non-western identities. In Susanna, P., Monika, H.S., Teijamari, J., Astrid, W. (eds) Encouraging collections mobility: a way forward for museums in Europe. Finnish National Gallery, Erfgoed Nederland & Institut für Museumsforschung, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin – Preussischer Kulturbesitz, pp. 236-245.

Chrisman, L. and Williams, P. (eds) (1993) Colonial discourse and post-colonial theory: A reader. Hertfordshire: Harvester Wheatsheaf.

Cooper, D., Locke, H. and Wood, J. (2004) Diana Cooper, Hew Locke. London: The Drawing Room.

Downey, A. (2014) Setting The Stage in Yinka Shonibare MBE. London: Prestel, pp. 43-46

Drayton, R (2019) Dziedzie, E., Tuite, D. and Watkins, J. (eds) Hew Locke here’s the thing. Birmingham: Ikon Gallery, p. 14.

Eddo-Lodge, R. (2017) Why I’m no longer talking to white people about race. London: Bloomsbury Publishing, p. 38.

Elkins, C. (2022) Legacy of violence: A history of the British Empire. London: The Bodley Head.

Hicks, D. (2020) The Brutish Museums: The Benin Bronzes, colonial violence and cultural restitution. London: Pluto press, pp. XIII-135.

Hooper-Greenhill, E. (ed.) (1997) Cultural diversity: Developing museum audiences in Britain. London: Leicester University Press, pp. 3-10.

Jackson, A. and Tomkins, D. (2011) Illustrating empire: A visual history of British imperialism. Oxford: Bodleian Library, p. 174.

Kent, R. (2014) Time and Transformation in the Art of Yinka Shonibare MBE in Yinka Shonibare MBE. London: Prestel, pp. 7-42

Kondile, U. (2021) “Ukuqhuqh Inkwethu yobuKoloniyali: Getting Rid of the Thick Layer of Colonial Dandruff on our heads,” in Mabaso, N. and Mistry, J. (eds) “Decolonial Propositions,” On curating , (49), p. 40.

Lejeune, R. (2018) “An Introductory Glossary for A Selective Guide To The V&A’s South Asian Collection,” in Tanya, A. (ed.) A Selective Guide To The V&A’s South Asian Collection. London: Delfina Foundation, pp. 9–17.

Lorde, A. (2019) “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House,” in Sister Outsider. London: Penguin Books, pp. 103–106.

Mabaso, N. and Mistry, J. (2021) “Introductory Comments: Initiatives and Strategies,” in Mabaso, N. and Mistry, J. (eds) “Decolonial Propositions,” On curating , (49), p. 5.

Marlowe, J. (1972) Cecil Rhodes: The Anatomy of Empire. London: Paul Elek.

Onciul, B. (2017) Museums, heritage and indigenous voice decolonising engagement. New York, N.Y: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, pp. 3-8.

Procter, A. (2021) The whole picture: The colonial story of the art in our museums & why we need to talk about it. London: Cassell.

Thardoor, S. (2017) Inglorious empire: What the British did to India. London: Penguin Books Ltd.

The British Museum (ed.) (2019) Re-imaging Captain Cook: Pacific perspectives. The British Museum Press, p. 6.

Woods, H.R., (2020). An act of history. New Statesman, 149(5524), p.18.

Journal articles

Atkin, L. (2015) “Looking at the other/seeing the self: Embodied performance and encounter in Brett Bailey’s Exhibit B and nineteenth-century ethnographic displays,” Safundi, 16(2), pp. 136–155. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/17533171.2015.1022415.

Auger, E. (2000) “Looking at native art through western art categories: From the ‘highest’ to the ‘lowest’ point of View,” Journal of Aesthetic Education, 34(2), p. 89. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/3333579

Bellentani, F. and Panico, M. (2016) “The meanings of monuments and memorials: Toward a semiotic approach,” Punctum. International Journal of Semiotics, 2(1), pp. 28–46. Available at: https://doi.org/10.18680/hss.2016.0004.

Burch‐Brown, J. (2020) “Should slavery’s statues be preserved? on transitional justice and contested heritage,” Journal of Applied Philosophy, 39(5), pp. 807–824. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/japp.12485.

Cammarota, J. (2011) “Blindsided by the avatar: White saviours and allies out of Hollywood and in Education,” Review of Education, Pedagogy, and Cultural Studies, 33(3), pp. 242–259. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/10714413.2011.585287.

Candido, M.P. (2020) “The expansion of slavery in Benguela during the nineteenth century,” International Review of Social History, 65(S28), pp. 67–92. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/s0020859020000140.

Cytlak, K. (2021) “Condensing vestiges of past futures in the Post-Peripheries: Artistic engagement with post-colonial and post-authoritarian contexts,” de arte, 56(1), pp. 23–45. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/00043389.2021.1968631.

Frost, S. (2019) “‘A bastion of colonialism’ – Public Perceptions of the British Museum and its Relationship to Empire”, Third Text, 33(4-5), pp. 487–499. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/09528822.2019.1653075.

Grant, C. and Price, D. (2020) “Decolonizing art history,” Art History, 43(1), pp. 8–66. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8365.12490

Gregory, J. (2021) Statue wars: collective memory reshaping the past, History Australia, 18:3, pp.564-587, Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/14490854.2021.1956333

Haebich, A. (2011) “Forgetting indigenous histories: Cases from the history of Australia’s stolen generations,” Journal of Social History, 44(4), pp. 1033–1046. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1353/jsh.2011.0042,

Hatt, M. (2022) “Counter-ceremonial: Contemporary artists and queen victoria monuments,” Victoria’s Self-Fashioning: Curating the Royal Image for Dynasty, Nation, and Empire, 2022(33), p. 3. Available at: https://doi.org/10.16995/ntn.4732.

Kluttz, J., Walker, J. and Walter, P. (2019) “Unsettling allyship, unlearning and learning towards Decolonising Solidarity,” Studies in the Education of Adults, 52(1), pp. 49–66. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/02660830.2019.1654591.

Lewis, M. (2018) “Until you see the whites of their eyes: Brett Bailey’s exhibit B and the consequences of staging the colonial gaze,” Theatre History Studies, 37(1), pp. 115–144. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1353/ths.2018.0007.

Macneil, R. P. (1999). Blackedout: The representation of Aboriginal people in Australian painting 1850-1900. PhD thesis, Department of Fine Arts, University of Melbourne, pp. 143 – 224. Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/11343/38917

Marschall, S. (2017) “Monuments and affordance,” Cahiers d’études africaines, (227), pp. 671–690. Available at: https://doi.org/10.4000/etudesafricaines.20860.

McLaren, A. and Clark, A. (2019) “Captain Cook upon changing seas: Indigenous Voices and reimagining at the British Museum,” The Journal of Pacific History, 55(3), pp. 418–431. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/00223344.2019.1663390.

Minott, R. (2019) “The past is now,” Third Text, 33(4-5), pp. 559–574. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/09528822.2019.1654206.

Plunkett, J. (2022) “A tale of two statues: Memorializing Queen Victoria in London and Calcutta,” Victoria’s Self-Fashioning: Curating the Royal Image for Dynasty, Nation, and Empire, 2022(33), pp. 2–32. Available at: https://doi.org/10.16995/ntn.6408.

Price, D. (2021) “Binding trauma,” Art History, 44(1), pp. 8–14. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8365.12572.

Samuel, C.A. and Ortiz, D.L. (2021) “‘method and meaning’: Storytelling as decolonial praxis in the psychology of racialized peoples,” New Ideas in Psychology, 62, pp. 1–11. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.newideapsych.2021.100868.

Santos, P.M. (2020) “Bringing slavery into the light in postcolonial Portugal,” Museum Worlds, 8(1), pp. 46–67. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3167/armw.2020.080105.

Sapega, E.W. (2008) “Remembering empire/forgetting the colonies: accretions of memory and the limits of commemoration in a Lisbon neighborhood,” History and Memory, 20(2), pp. 18–38. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2979/his.2008.20.2.18.

Steele, S. (1990) “White Guilt,” The American Scholar, 59(4), pp. 497–506. Available at: https://shibbolethsp.jstor.org/start?entityID=https%3A%2F%2Fidp.lboro.ac.uk%2Fsimplesaml%2Fsaml2%2Fidp%2Fmetadata.php&dest=https://www.jstor.org/stable/41211829&site=jstor

Tartir, A. (2016) Palestine-Isreal: Decolonization Now, Peace Later, Mediterranean Politics, 21:3, 457-460. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/13629395.2015.1126391

Tuck, E. and Yang, K.W. (2012) “Decolonization is not a metaphor,” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 1(1), pp. 1–40. Available at: https://www.ed.ac.uk/files/atoms/files/tuck_and_yang_2012_decolonization_is_not_a_metaphor.pdf.

Wajid, S. and Minott, R. (2019) “Detoxing and decolonising museums,” Museum Activism, pp. 25–35. Available at: https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351251044-3.

Wintle, C. (2013) ‘Decolonising the Museum: The case of the Imperial and Commonwealth Institutes’, Museum and Society, vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 185-201. Available at: https://journals.le.ac.uk/ojs1/index.php/mas/article/view/232>

Websites

Baksh, M. (2022) Hew Locke’s quiet radicalism, ArtReview. Available at: https://artreview.com/hew-lockes-quiet-radicalism/ (Accessed: December 24, 2022).

BBC (n.d.) A history of the world – object: Ife head, BBC. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/ahistoryoftheworld/objects/Z1CgMudYTJWzpTi-TW1IAA#:~:text=This%20naturalism%20astonished%20art%20historians,brought%20to%20Europe%20in%201911. (Accessed: November 27, 2022).

Busari, S. (2010) The African sculptures mistaken for remains of Atlantis, CNN. Cable News Network. Available at: http://edition.cnn.com/2010/WORLD/africa/06/21/kingdom.ife.sculptures/index.html (Accessed: October 17, 2022).

Canales, K. (2021) Fabric of the African diaspora, V&A Blog. V&A. Available at: https://www.vam.ac.uk/blog/museum-life/fabric-of-the-african-diaspora (Accessed: November 27, 2022).

Chaudhuri, A. (2016) The real meaning of Rhodes must fall, The Guardian. Guardian News and Media. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2016/mar/16/the-real-meaning-of-rhodes-must-fall (Accessed: December 20, 2022).

Cielatkowska, Z. (2020) Decolonising art criticism, Kunstkritikk. Nordic Art Review. Available at: https://kunstkritikk.com/decolonising-art-criticism/#:~:text=Decolonising%20the%20art%20institution%20usually,not%20the%20same%20as%20diversity). (Accessed: October 15, 2022).

Commonwealth sport (n.d.) Foreign Exchange, Commonwealth Games – Birmingham 2022. Available at: https://www.birmingham2022.com/festival/2498787/foreign-exchange (Accessed: December 18, 2022).

Fernandes, G.N. (2020) Memorial in Lisbon: Recovering history that was made invisible, Contemporary &. Available at: https://contemporaryand.com/fr/magazines/memorial-in-lisbon-recovering-history-that-was-made-invisible/ (Accessed: December 25, 2022).

Hasinah, A. (2022) “Notes on ‘Decolonising the Curatorial’ in Babylon Britain.”. Medium. Available at: https://medium.com/@aliyahhasinah/notes-on-decolonising-the-curatorial-in-babylon-britain-cd9877d52f81 (Accessed: January 11, 2023).

Holloway, L. (2014) Barbican accused of ‘complicit racism’ over installation with live black models, The Guardian. Guardian News and Media. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2014/aug/28/exhibition-b-barbican-protest-petition (Accessed: January 2, 2023).

Ilori, Y. and Shonibare, Y. (2021) “‘I don’t care what people think. As artists, we have to express ourselves’: Yinka Ilori in conversation with Yinka Shonibare,” It’s nice that. Available at: https://www.itsnicethat.com/features/yinka-shonibare-yinka-ilori-in-conversation-art-290621 (Accessed: December 30, 2022).

Irwin, R. (2015) Decolonization, University at Albany. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.library.albany.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1024&context=history_fac_scholar (Accessed: January 2, 2023).

Jasanoff, M. (2020) Misremembering the British empire, The New Yorker. Available at: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2020/11/02/misremembering-the-british-empire (Accessed: December 23, 2022).

Jeffries, S. (2022) Stop tearing down controversial statues, says British-guyanan artist Hew Locke, The Spectator. Available at: https://www.spectator.co.uk/article/stop-tearing-down-controversial-statues-says-british-guyanan-artist-hew-locke/ (Accessed: December 18, 2022).

John, E. (2022) Black artists highlight how the trauma of Empire still echoes in Britain, CNN. Cable News Network. Available at: https://edition.cnn.com/style/article/lubaina-himid-yinka-shonibare-spc-intl/index.html (Accessed: November 28, 2022).

Kassim, S. (2017) The museum will not be decolonised. Media Diversified. Available at: https://mediadiversified.org/2017/11/15/the-museum-will-not-be-decolonised/ (Accessed: November 7, 2022).

Lança, M. (2019) De/Re-Memorization of Portuguese Colonialism and Dictatorship: Re-Reading the Colonial and the Salazar Era and Its Ramifications Today, Mezosfera.org. Mezosfera. Available at: http://mezosfera.org/de-re-memorization-of-portuguese-colonialism-and-dictatorship-re-reading-the-colonial-and-the-salazar-era-and-its-ramifications-today/ (Accessed: December 25, 2022).

Lawler, A. (2020) Pulling down statues? it’s a tradition that dates back to U.S. independence. National Geographic. Available at: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/article/pulling-down-statues-tradition-dates-back-united-states-independence (Accessed: December 13, 2022).

Marty, S. (2020) Decolonising public space? The London Moment. Hypotheses. Available at: https://exilegov.hypotheses.org/2278 (Accessed: December 11, 2022).

McAloon, J. (2018) Understanding Donatello’s “David” as a work of Gay Art, Artsy. Artsy. Available at: https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-point-one-worlds-famous-sculptures (Accessed: November 27, 2022).

Morris, K. (2020) Marc Quinn’s black lives matter statue is not Solidarity. ArtReview. Available at: https://artreview.com/marc-quinn-black-lives-matter-statue-is-not-solidarity/ (Accessed: December 30, 2022).

O’Loughlin, M. (2020) The stolen generation. The Australian Museum. Available at: https://australian.museum/learn/first-nations/stolen-generation/ (Accessed: November 20, 2022).

Odunlami , S. and Andrews, K. (2014) Is art installation exhibit B racist?, The Guardian. Guardian News and Media. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2014/sep/27/is-art-installation-exhibit-b-racist (Accessed: January 1, 2023).

Plasencia, I. (2021) Who are they if we’ve already left? who are we if they’re still here?, A*Desk. Available at: https://a-desk.org/en/magazine/who-are-they-if-weve-already-left-who-are-we-if-theyre-still-here/ (Accessed: December 25, 2022).

Queensland Art Gallery of Modern Art (n.d.) Civilised #1, #2, #6, #10 – Michael Cook. Queensland Art Gallery of Modern Art. Available at: https://learning.qagoma.qld.gov.au/artworks/civilised-1-2-6-10/ (Accessed: November 19, 2022).

Qureshi, S. (2014) Exhibit B puts people on display for Edinburgh International Festival, The Conversation. Available at: https://theconversation.com/exhibit-b-puts-people-on-display-for-edinburgh-international-festival-30344 (Accessed: January 2, 2023).

Reid, N. (2021) No more white saviours, thanks: How to be a true anti-racist ally, The Guardian. Guardian News and Media. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/sep/19/no-more-white-saviours-thanks-how-to-be-a-true-anti-racist-ally (Accessed: December 31, 2022).

Ross, E. (2019) The past is still present: Why colonialism deserves better coverage. The Correspondent. Available at: https://thecorrespondent.com/32/the-past-is-still-present-why-colonialism-deserves-better-coverage (Accessed: January 26, 2023).

Shonibare, Y. (n.d.) Biography. Yinkashonibare.com. Available at: https://yinkashonibare.com/biography/ (Accessed: January 23, 2023).

Solso, R.L. (2004) About faces, in art and in the brain, Dana Foundation. Dana Foundation. Available at: https://dana.org/article/about-faces-in-art-and-in-the-brain/ (Accessed: November 28, 2022).

Sousa, A.N.de (2021) How Portugal silenced ‘centuries of violence and trauma’, History, Al Jazeera. Available at: https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2021/3/10/how-portugal-silenced-centuries-of-violence-and-trauma (Accessed: December 28, 2022).

Stevens, M.C. (2019) When white “allies” go wrong, Hyperallergic. Available at: https://hyperallergic.com/509063/when-white-allies-go-wrong/ (Accessed: December 30, 2022).

Stooke, A. (2019) Captain Cook Reimagined from the British Museum’s Point of View. Third Text. Available at: http://thirdtext.org/stooke-cook-britishmuseum (Accessed: November 21, 2022).

Tate (2019) Kiluanji Kia Henda – ‘I Wanted to Create a Trap’, YouTube. YouTube. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6SMZ9MS6aoE (Accessed: December 25, 2022).

Timalsina, T. (2021) Why Rhodes Must Fall, Harvard Political Review. Available at: https://harvardpolitics.com/rhodes-must-fall/ (Accessed: December 13, 2022).

Wall, T. (2020) Jen Reid: ‘I felt a surge of power. Colston is gone. now there’s a new girl in town’, The Guardian. Guardian News and Media. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/dec/06/jen-reid-bristol-black-lives-matter-colston-marc-quinn-faces-of-2020 (Accessed: December 31, 2022).

Windholz, A. (2020) Unpacking white saviourism, Medium. Medium. Available at: https://anniewindholz.medium.com/unpacking-white-saviorism-7d7b659dcbb3 (Accessed: January 19, 2023).

Online videos

Aburawa, A. (2018) The Museum will not be decolonised. Vimeo. Available at: https://vimeo.com/302162709 (Accessed: December 4, 2022).

Cook, M. (2018) Michael Cook discusses his art practice and ‘Civilised’. QAGOMA. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pyIi3O0G6rY&t=1s (Accessed: November 19, 2022).

Hasinah, A. (2020) Decoloniality: A home for us all. TEDx Talks. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NooGomxpCI8 (Accessed: January 11, 2023).

Ikon Gallery (2022) Hew locke – Foreign Exchange . YouTube. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Is6-F0txOW0 (Accessed: December 8, 2022).

Intelligence Squared (2018) Revere or Remove? The Battle Over Statues, Heritage and History. YouTube. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SoC2ioaQUQU (Accessed: December 8, 2022).

Lamoureux, K. (2022) A Beginner’s Guide to Decolonization. TEDx Talks. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GFUwnMHN_T8 (Accessed: January 11, 2023).

Mohamedi, G.(2018) Screaming in the Silence: How to be an ally, not a savior. YouTube. TEDxTalks. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d2qAbp-t_FY (Accessed: December 30, 2022).

Shaheen, K. (2018) Decolonising display, MuseumNext, Vimeo. Available at: https://vimeo.com/277609160 (Accessed: January 1, 2023).

Shonibare, Y. (2020) Earth Kids. James Cohen. Available at: https://www.jamescohan.com/artists/yinka-shonibare-cbe/featured-works?view=slider#25 (Accessed: November 15, 2022).

Podcasts

Fennell, M. (2021) “Not your Venus,” Stuff the British stole. [podcast]. ABC. Available at: https://open.spotify.com/episode/2FqhgNwYNb8qLejogImSxm?si=QrAUbqyDTg6c_bQAcWYUvA&utm_source=copy-link (Accessed: January 18, 2023).

Green, J. (2021) Episode 8: Are you a White Ally or a White Saviour?, Go Smudge Yourself, The Landback podcast. Spotify. Available at: https://open.spotify.com/episode/1QX5oVrvqIseflZBP2Bg4m?si=9160ccb1ae9a4f94 (Accessed: January 20, 2023).

Lennard, L., Murray, C. and Kosmalska, V. (2019) Reimagining Captain Cook: Pacific Perspectives at the British Museum. The Artcast. [Podcast]. Available at: https://open.spotify.com/episode/1mTFFWVSwuTWiNnJwxhTTY?si=77d87a4f1e1b449d (Accessed: November 20, 2023)

Artworks/images

Cook, M. (2012) Civilised #12. [Inkjet print]. This is no fantasy gallery, Melbourne. Available at: https://www.michaelcook.net.au/projects/civilised

Henda, K.K. (2021) Plantation. [Aluminium]. Campo das Cebolas, Lisbon. Available at: https://www.memorialescravatura.com/

Locke, H. (2022) Foreign exchange. [Resin sculpture]. Birmingham. Photographed by Shaun Fellows. Available at: https://artreview.com/hew-lockes-quiet-radicalism/

Quinn, M. (2020) A Surge of Power [Resin] Bristol. Available at: http://marcquinn.com/studio/news/a-joint-statement-from-marc-quinn-and-jen-reid

Shonibare, Y. (2021) Unintended Sculpture (Donatello’s David and Ife head). [Fibreglass sculpture]. Stephen Friedman Gallery, London. Photographed by Stephen White & Co. Available at: https://yinkashonibare.com/artwork/unintended-sculpture-donatellos-david-and-ife-head/

The Past is Now: Birmingham and The British Empire (2017) [exhibition], Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery, Birmingham, 2017-2018. Available at: https://www.shaheenkasmani.com/the-past-is-now